The new methods of “big data” analysis can inform and expand historical analysis in ways that allow historians to redefine expectations regarding the nature of evidence, the stages of analysis, and the claims of interpretation.1 For historians accustomed to interpreting the multiple causes of events within a narrative context, exploring the complicated meaning of polyvalent texts, and assessing the extent to which selected evidence is representative of broader trends, the shift toward data mining (specifically text mining) requires a willingness to think in terms of correlations between actions, accept the “messiness” of large amounts of data, and recognize the value of identifying broad patterns in the flow of information.2

The new methods of “big data” analysis can inform and expand historical analysis in ways that allow historians to redefine expectations regarding the nature of evidence, the stages of analysis, and the claims of interpretation.1 For historians accustomed to interpreting the multiple causes of events within a narrative context, exploring the complicated meaning of polyvalent texts, and assessing the extent to which selected evidence is representative of broader trends, the shift toward data mining (specifically text mining) requires a willingness to think in terms of correlations between actions, accept the “messiness” of large amounts of data, and recognize the value of identifying broad patterns in the flow of information.2

Continue reading…

When

When

The new methods of “big data” analysis can inform and expand historical analysis in ways that allow historians to redefine expectations regarding the nature of evidence, the stages of analysis, and the claims of interpretation.

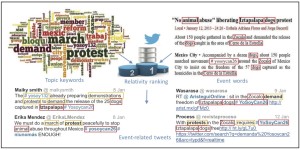

The new methods of “big data” analysis can inform and expand historical analysis in ways that allow historians to redefine expectations regarding the nature of evidence, the stages of analysis, and the claims of interpretation. Congrats to C.T-Lu and his students whose paper on finding the breadcrumbs of civil unrest on Twitter has been picked as a Jan 2014 highlight by the IEEE Special Technical Community (STC) on Social Networking! For more details visit here

Congrats to C.T-Lu and his students whose paper on finding the breadcrumbs of civil unrest on Twitter has been picked as a Jan 2014 highlight by the IEEE Special Technical Community (STC) on Social Networking! For more details visit here